Reality Distortion is Swallowing Our Technology, Our Politics, and Our Lives

Fighting It Is An Individual Decision With Potentially Global Consequences

At LiteralMayhem, we don’t do hot takes. We step back, pause, and rethink.

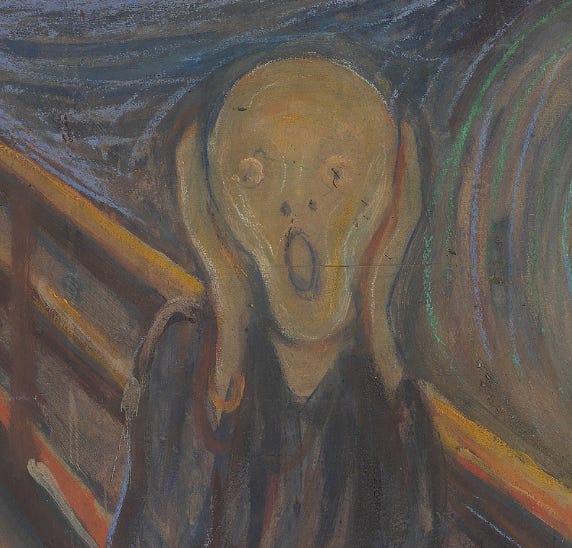

Popular narratives can create—as we’ll see later in this piece—something called a “reality distortion field,” an immersive sense of reality that, while it feels true, is not actually true in an objective sense. In fact, the distortion field pushes us toward a “shunning” of the truth.

When immersed in a reality distortion field, we lose our bearings; it swallows our ability to see and resist it. And breaking through a reality distortion field is tricky business that requires effort and thought.

Stepping back, pausing and rethinking.

The first thing to know about a reality distortion fields is that, although it can feel like irresistible “social drift,” to quote George Orwell, it doesn’t happen by accident.

One of my favorite writers these days is William Finnegan of The Long Memo, who feels like a kindred spirit in his recognition of just how bad things are getting, as well as the terrible truth that it’s likely to get much worse before it gets better.

He also recognizes the intentionality of the decline. Last week in Persuasion he wrote [emphasis added]:

“The real culture war isn’t between right and left. The real culture war is between those trying to preserve any form of ordered liberty and those, knowingly or not, pushing toward collapse… What too few acknowledge is that collapse isn’t purely organic. It is being curated. Incentivized. Profited from.”

He warned that both left and right are vulnerable to anti-democratic urges because we all swim in the “same poisoned waters.”

Here is the key point: Finnegan’s “poisoned waters” is what others have called a “reality distortion field.”

Today, we are fighting many reality distortion fields, with potentially epochal consequences and unimaginable political and financial gains for the already powerful. Two of the biggest ones being…

AI hype, which is raining cash down onto AI’s elite owners, while also transforming government, industry, academia, and media in real-time—to potentially rain more cash down on billionaire techbros at the expense of civil society.

Disinformation and misinformation that spins political abnormality as merely a different version of normal, i.e., sanewashing the political chaos and cruelty, while power accrues to the few at the expense of the many.

By now, human beings should know how to avoid hype bubbles and the reality distortion they create. We sure have enough history with them.

But we can’t seem to find a way to stop them before they inflate and blow up.

Several weeks ago, in The Big Picture, Barry Ritholtz made a pointed observation about how little we learn from history, especially in the area of self-restraint.

He says about history’s quintessential bubble, the Tulip Craze:

“We have learned much about how people behave when the potential gains are huge. What we have not learned over those centuries is how to manage our own behavior.”

We have seen how human behavior creates hype bubbles, and we have seen the results when they explode. The Tech Bubble burst in 2001; it’s now called the Dot-Com Crash. The mortgage bubble burst in 2008; it’s now called the Great Financial Crisis.

In both cases hypsters led the charge, and the consequences were dire. In the latter case, causing acute global pain, even to those who did not participate in inflating the bubble.

In neither case was there any commensurate level of accountability for the bubble inflators—the reality distorters—the relative few who profited immensely at the expense of the many.

Here’s another example of a reality-distorting hype bubble that brought dire consequences for the world: the Iraq War.

Here, we can’t (and won’t) even attempt to summarize all the analysis previously written about the lead-up to the Iraq War.

Our purpose here is to home in on a single aspect: the role of professional storytellers in distorting reality to the point that it leads to disastrous consequences for us all.

By the time the hype bubble burst—and the reality distortion field dissipated—the war had caused vast devastation, left 37K+ dead and wounded Americans, 200K+ dead Iraqi civilians, with a cost, so far, of $3 trillion, including veterans’ care. It left behind an environmental catastrophe of destroyed forests, military waste, uncontained toxic chemicals, and millions of hectares of land unusable because of landmines.

It also offered a snapshot of the role of spinmeisters in inflating hype bubbles: one poignant example being the role of former Bush administration spokesman Scott McClellan, who published a pseudo-confessional book back in 2008 called What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington's Culture of Deception.

Rather than reviewing the book itself, what’s more helpful is to have a look at a review of the book from the time it was published… an article that crystalizes the reality-distorting, ethical failures of professional storytellers, in all their icky glory.

Narrative Hype Bubbles Are “Reality Distortion Fields”

When it was published, McLellan’s book was reviewed by an award-winning publication of The Center for Media & Democracy called PRWatch (now called Exposed by CMD).

That short review, by PRWatch co-editor Sheldon Rampton, is very much worth a quick read, if you’re so inclined.

In his review, Rampton quotes a former PR pro named John Stoddard (who was later convicted of 11 counts of defrauding his clients): Stoddard pinned the boosterism of the Iraq War on McClellan’s personal failure, rather than a failure of the PR profession itself.

Stoddard argued that [emphasis added]…

There is no more high-profile PR job in the United States... Scott McClellan defined the PR profession downward during his misbegotten tenure, and has done further damage with this book. ... McClellan asks us, in so many words, not to expect integrity from him, or anyone else who does what he does for a living. McClellan doesn't explain how he changed his mind about Bush, Iraq or anything else. He doesn't confess to intentionally lying. He just wants you to understand you should never have believed the things he said.

Rampton’s review also quotes Greg Mitchell, former editor of Editor & Publisher, lambasting the press for an...

… orgy of coverage of the fifth anniversary of the start of the Iraq war [in which] the media reviewed every aspect of the war and pointed fingers everywhere, except at the media. There was almost no self-assessment, after five years of war.

Fine. Both are true. The hype bubble that led to the Iraq War was a personal failure of McClellan, of course, and it was a failure of the media, of course.

But in his book, McClellan contends that a conspiracy of silence was also to blame. And this is where things get a bit sticky.

According to McLellan, the undertow of the story—about WMDs and a link to 9/11—was too strong a narrative current to resist. It was just too powerful, and it sucked them all under. McClellan’s rationalization is that most people in Washington are:

…good, decent people [who have] made a practice of shunning truth and the high level of openness and forthrightness required to discover it.

Greg Mitchell’s retort:

Is this what good, decent people do? If they shun the truth doesn’t that make them liars?... What [McClellan’s] describing is epistemologically tricky. If you're not conscious of lying, then by definition you're not lying.

Rampton, of PRWatch, offered his own assessment of the epistemology of lying [emphasis added]:

This is a valid point, but what it misses is the way ‘spin’ creates a reality distortion field which makes it possible for its practitioners to deceive even themselves in the act of deceiving…

The White House found ways of creating the appearance of a relationship between Iraq and 9/11, while being careful not to actually say so specifically. This is the essence of spin, bluffing, or bullshitting if you prefer to call it that. And it turns out that a great deal can be accomplished by way of deceiving people, without necessarily telling specific, nailable lies.

For obvious reasons, politicians prefer this approach whenever possible, but in the process, they create an environment -- McClellan calls it a ‘permanent campaign’ -- which he makes the distinction between truth and falsehood indiscernible, even (and in fact especially) to the spinners themselves. They can therefore ‘shun the truth’ without seeing themselves as liars and later claim that they were not ‘willful or conscious’ of what they were doing.

Rampton leaves off by asking:

How do we find our way back from this world into a world where politics is played according to rules of genuine honesty and candor? That, of course, is a big question, but it needs to be answered. McClellan's confessions -- but more importantly, the debacle in Iraq itself -- point to the need for reform in multiple arenas: in politics, in journalism, and in the way public relations operators spin the news.

Sound familiar?

Does it feel like, today, we have successfully implemented “reform” in politics, journalism and the way PR people spin the news?

It does not. If anything, reality distortion is worse than ever.

We know how people behave when there is much to gain. We see it in our current hype cycles. We clearly see it in historical examples.

But we have learned little to nothing about how to control our own behavior such that we know how to adhere to “rules of genuine honesty and candor” in the face of an inflating hype bubble, and an intentional distortion of reality by those with something to gain.

“Spin” Is A Kind of Reality Distortion: Asserting Truth While Leaving A False Impression.

McLellan’s story illustrates the personal incentives and mechanics of how spin gets manufactured, circulated, bought-into by the public and the media, and then disavowed by those who did the deed.

Was it all lies? In defense of the PR profession, Stoddard says that good PR people never lie and tell their clients never to lie.

But misdirection, well, that’s another story. Stoddard says:

“‘Spin’ refers to the artful selection of words so that the listeners or readers are left with the impression the speaker desires them to have. For ‘spin’ to work, every word has to be true.”

And there is the confession: the art of “spin” is using truth to leave an impression that may or may not be true, which makes no difference to the spinner as long as the listener is persuaded.

In McClellan’s case, his “spin” used assertions he didn’t bother to verify, to leave an impression that was ultimately false. Just as Rampton had said. McLellan was “deceiving people without telling specific nailable lies.”

In the case of his own behavior, McClellan failed even the most basic test of trying to figure out whether his statements were actually true—he was “shunning the truth” while not intentionally lying.

This case, in miniature, is exactly what we’re seeing in the hype around AI—a technology that could forever change the course of human society.

Boosters inflate its potential benefits beyond reason while, relatively speaking, they and the press give almost no air at all to its enormous potential harms—a bubble of reality distortion with potentially civilizational consequences.

That “spin” leaves a broad impression with the public that AI is safe, with manageable risks and responsible people at the helm. AI boosters would deny accusations that they’re telling specific “nailable” lies, even while the totality of their “spin” leaves the audience with an impression that’s demonstrably false.

We’re seeing the same kind of narrative bubble and reality distortion around the normalization of autocratic political extremism, couching an overthrow of democratic norms in the rhetoric of normal politics—talking about it like it’s just a different kind of politics, and a different managerial approach to governing.

Intentional spin combined with press timidity allows the bubble to keep inflating, in what can only be described as a reality distortion field.

And within that distortion field, the feeling and sensibility around normalcy shifts. The distortion field too often prevents us from seeing, never mind admitting, what’s happening. And that’s how we end up with good people “shunning truth and the high level of openness and forthrightness required to discover it.”

When living in a reality distortion field, there is no incentive to challenge it, because challenges are rebuffed, emphatically, often at great personal cost to the challengers.

Defeating A Reality Distortion Field Is A Long Difficult Slog

For an exhaustive and wonderfully cranky piece on the frustration of trying to pop AI’s narrative bubble—and neutralize the reality distortion field around that technology—you can read Ed Zitron’s article The Generative AI Con.

“My heart darkens, albeit briefly, when I think of how cynical all of this is. Corporations building products that don't really do much that are being sold on the idea that one day they might, peddled by reporters that want to believe their narratives — and in some cases actively champion them. The damage will be tens of thousands of people fired, long-term environmental and infrastructural chaos, and a profound depression in Silicon Valley that I believe will dwarf the dot-com bust.

“And when this all falls apart — and I believe it will — there will be a very public reckoning for the tech industry.”

Paul Krugman is a great example of someone shaking the political distortion field, trying to break the sense of “normalcy” it creates:

“So what should those of us who would like America to remain America, to not see us descend into dictatorship, be doing?

“First, acknowledge the reality. If my use of the word ‘dictatorship’ disturbs you, if your first reaction is to say ‘Isn’t that a bit shrill?’, you’re part of the problem. The constitutional crisis isn’t something that might hypothetically happen; it’s fully underway as you read this.”

And for context, here’s a throwback moment: back in 1946, George Orwell felt that the fiction-writing profession was living through a kind of a narrative bubble—a distortion field around the acceptability of totalitarianism, pushed by a Russophile intellectual elite. In an article in Polemic Magazine, he wondered [emphasis added]…

“When one sees highly educated men looking on indifferently at oppression and persecution, one wonders which to despise more, their cynicism or their shortsightedness…

“In our age, the idea of intellectual liberty is under attack from two directions. On the one side are its theoretical enemies, the apologists of totalitarianism, and on the other its immediate, practical enemies, monopoly and bureaucracy. Any writer or journalist who wants to retain his integrity finds himself thwarted by the general drift of society rather than by active persecution…

“A totalitarian society which succeeded in perpetuating itself would probably set up a schizophrenic system of thought, in which the laws of common sense held good in everyday life and in certain exact sciences, but could be disregarded by the politician, the historian, and the sociologist. Already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific textbook, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying an historical fact. It is at the point where literature and politics cross that totalitarianism exerts its greatest pressure on the intellectual.”

Does the Orwell quote a feel bit too much? Too heavy? Too coldly historical?

It’s not.

We are currently living in a “schizophrenic system of thought,” just as he did: driven by corrupt storytelling in which a common sense that prevails in daily life is swallowed by an intentional distortion of reality.

(And not for nothin, the attacks by this administration on scientific facts defy even Orwell’s notion of a scandal too far.)

For their part, AI companies have been able to manipulate markets, strong-arm regulators, woo legislators, and bamboozle businesses and consumers, by spinning false impressions around AI’s current capabilities and destiny.

They have created an “enforced orthodoxy” (Orwell’s words), and at this point, challenging that dominant storyline is not permitted. It earns you only contempt and a backlash from the distortion field, with the aim of intimidation and instilling a sense of FOMO.

A similarly powerful reality distortion field rebuffs any call to name our current U.S. regime for what it is.

A brave few make the effort: Scholar of tyranny Timothy Snyder says, “Of course it’s a coup,” as does Robert Reich. Krugman calls it an “autogolpe,” or a self-coup. Max Boot, as far back as August 2020, was calling Trump 1.0 a “criminal conspiracy;” just as The Long Memo does today with Trump 2.0.

But the mainstream media, thus far, have been loath to call it what it is.

Whatever you call it, you cannot call it “normal.” In truth, we are now living within a right-wing “permanent campaign” of reality distortion—i.e., a “schizophrenic system of thought” in which the clear dismantling of democratic norms is spun as simply politicians doing politician stuff, a different and unorthodox way of doing politics.

(Well actually, that last statement is kinda true-ish, in a tautological way. See how misleading true assertions can be?)

Outliving Our Current “Schizophrenic System of Thought”

Once we get past these crises, even if it takes years (decades?), we’ll look back and understand what Stoddard did about McClellan’s Iraq War “spin”…

It’s something we should know by now about every bubble maker, and every professional hypester. When it’s all over and the hypster is called to account:

He doesn't confess to intentionally lying. He just wants you to understand you should never have believed the things he said.

We are living today during an accumulation of deceit and misdirection. Some of it based on bald-faced lies. But much of it based on a systematic building of true (ish) assertions into demonstrably false impressions—into a reality distortion field.

Those efforts are, in large part, aided and abetted by the failure of news media (of all stripes) to challenge those assertions effectively.

What Philip Bump wrote in the Washington Post could apply just as easily to the AI hype bubble as it does to the normalizing of today’s political extremism. According to Bump [brackets are my additions]:

This is not a great way to run a democracy — to build a contingent of tens of millions of people who reject the world as it is in favor of the way a [president or CEO] demagogue and his allies want it to be… It is a much worse way to run a government [or a society]. And yet here we are.

In Rampton’s words, how do we get back to “rules of genuine honesty and candor?” He admits it’s a big question, and one that needs to be answered.

But to quote Ritholtz once more:

We have learned much about how people behave when the potential gains are huge. What we have not learned over those centuries is how to manage our own behavior.

Right now, the potential gains from reality distortion are not only clear, but also beyond any scale previously imaginable. Hyperinflation of these reality-distorting narrative bubbles is still accelerating because the potential gains are so fucking huge. Not just in political and financial rewards, but also in control of discourse, perception, and maybe even reality itself.

Eventually such bubbles collapse under their own weight. We can only hope. The problem is that, along the way, a lot of bystanders get lured in; they take the moral equivalent of a zero-down, no-doc, interest-only loan on our shared future. Just so they can plunk down some chips and maybe win a round or two of the big game.

Then, when it all collapses into a steaming pile of financial, political, and social wreckage, tens of millions if not billions of innocents get crushed under the rubble.

What have we learned?

Reality distortion is a highly rewarding gig, and we cannot count on incentivized hypsters to resist its Siren call. We also cannot count on being saved by most of those in the media who get paid to see through the hype and burst the reality distortion bubble. No matter the reason, too often they refuse, or just fail.

It is up to each of us, in our own way, to “manage our own behavior” within the general drift of society and challenge the reality distortion field as honestly as we can: refuse to buckle under its pressure and maintain a “high level of openness and forthrightness” required to ferret out the truth and then share it.

All the while hoping and praying that, just maybe, for this one time, when the bubble bursts there will be accountability for the fraudulent storytellers and spinners—accountability beyond empty mea culpas that admit nothing, avoiding all blame and accountability.

Next Wednesday we will host our first podcast episode.

Our guest will be Andreu Belsunces Gonçalves, a co-founder of the Hype Studies Group, and a lecturer in Science and Technology Studies at Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, where he focuses on the relation between socio-technical fictions, power, and technology. He is also an organizer of the Hype Studies Conference to be held in Barcelona in September 2025.

Brilliant discussion, explains so much about politician-speak!